FEATURED

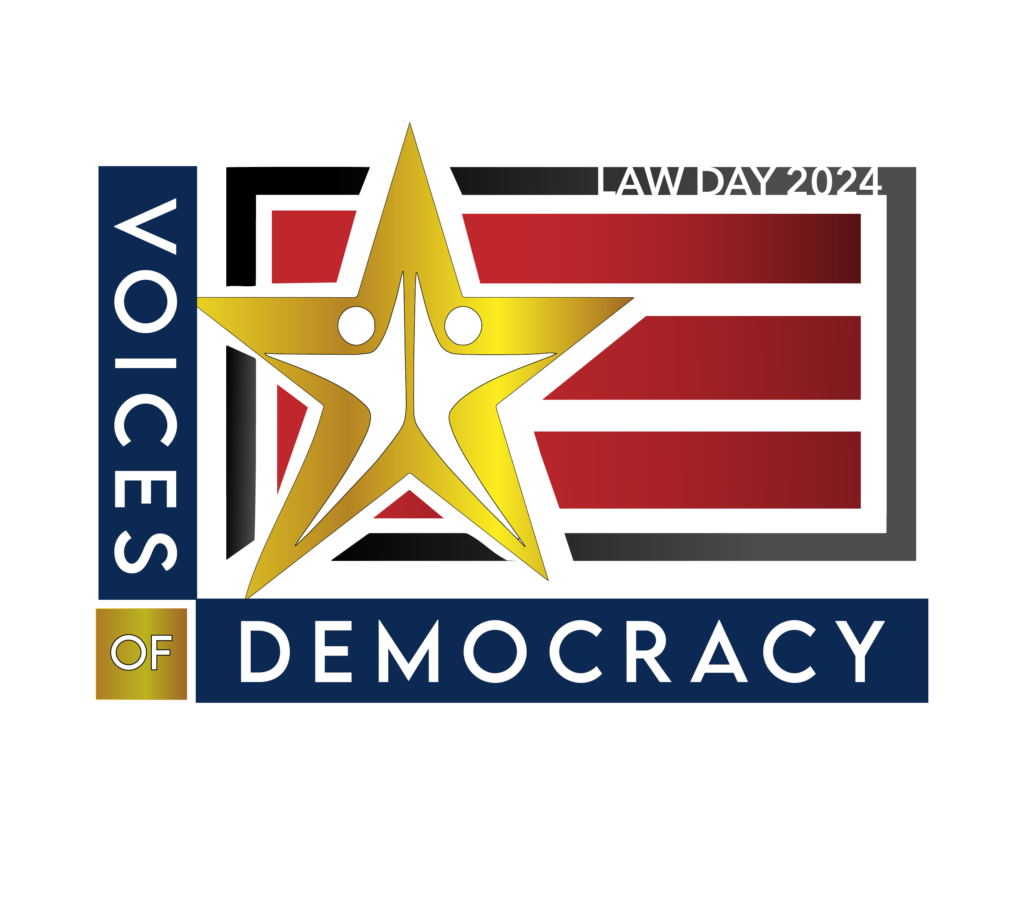

Law Day 2024

The Voices of Democracy Law Day theme encourages Americans to participate in the 2024 elections by deepening their understanding of the electoral process

On the Docket

The ABA Division for Public Education is hosting a free online Supreme Court preview panel in partnership with the American University Washington College of Law on Thursday, September 28, 2023 from 12pm - 1:30pm.

FEATURED RESOURCES

These resources were developed by the ABA Division for Public Education. They include lessons plans, programs, publications and information on professional development.

Programs

Virtual moderated panel discussion programs

Classroom Resources

Give your students basic understanding about the law.

Legal FAQs

Learn about legal FAQs, legal documents and court processes.

PUBLICATIONS

Looking for resources on the Supreme Court, teaching civics or the rule of law? Or for teacher professional development? We offer a variety of publications and resources to help advance the rule of law.

PREVIEW of the U.S. Supreme Court

PREVIEW is an eight-issue subscription publication that provides expert, plain-language analysis of all cases given plenary review by the Supreme Court in advance of oral argument. Preview issues 1-7 precede the Court’s seven argument sessions from October to April.

Insights on Law & Society

Insights on Law & Society is a magazine for social studies teachers (especially of civics, government, history, and law in grades 6-12). Each issue of Insights explores a law-related topic from several angles, provides lesson ideas, and highlights real life students and practitioners.

The Division for Public Education provides reliable information about the law and legal issues, including resources and programs for educators, students, journalists, legal professionals, opinion leaders, and the public to advance public understanding of law and its role in society.